Out of the Asylums and Into the Army:

PSYCHIATRY CREATES

MULTI-BILLION DOLLAR MARKET

For Military Psychiatrists and Big Pharma

The mental health watchdog Citizens Commission on Human Rights announces the third in a four-part series by award-winning investigative journalist Kelly Patricia O’Meara exploring the epidemic of suicides and sudden deaths in the military and the skyrocketing use of psychiatric drugs being prescribed to soldiers and vets. The third installment looks at the historical data behind the psychiatric-military alliance and the psychiatric-pharmaceutical industry’s increasing power and influence within the military today.

“War is hell.” Few who have served in combat would argue with this summation of the brutality and human tragedy of battle, provided long ago by Civil War General, William Tecumseh Sherman.

Acknowledging the sacrifice of our troops, as a nation, we welcome the returning warriors as heroes, making it all the more difficult to understand why the psychiatric community seems determined to make victims of the very soldiers we honor for their extraordinary service.

As has been well documented in the first two parts of this investigative series, the military is at a mental health crossroad. Soldiers are dying by suicide and other sudden unexplained deaths at record—even epidemic—levels; an epidemic that seems to have been spawned by the nearly $2 billion Department of Defense (DoD) and Veterans Affairs (VA) have spent on antipsychotics and anti-anxiety drugs, despite international drug regulatory warnings of mania, psychosis, suicide and death. Even according to DoD’s own policy, “Guidance for Deployment-Limiting Psychiatric Conditions and Medications,” antipsychotics like Seroquel are disqualifiers for deployment.

Given that under the advice of mental health professionals suicides and other unexplained deaths still are increasing, why does command continue to listen to what, for all practical purposes, appears to have miserably failed? Despite the fact that since 2009, mental health staffing has doubled in Afghanistan and a mental health survey of deployed troops found that stress levels among service members in Afghanistan nearly tripled between 2005 and 2010.

To understand why command appears to be content with the nation’s troops being diagnosed as mentally ill and then, like freshmen at a frat keg party, plied with multiples of psychiatric drugs, one first must understand the psychiatric community’s ever-increasing interest in, and role, among the military ranks. It isn’t tough and military brass need only look back a few wars ago.

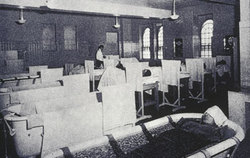

Prior to World War I virtually all American psychiatrists worked in mental asylums where there were no specific treatment methods for any given mental illness. In fact, some methods were so torturous the word “treatment” can’t be used to describe them.

For example: ice baths, where mental patients were submerged in freezing water until they lost consciousness; and bleedings, where a massive amount of blood was drained from the patient, often causing death.

However horrific psychiatry’s early treatment methods were, with war looming, for psychiatrists it was out of America’s asylums and into the Army where hospital white was replaced by officer rank Army green.

Psychiatrists previously employed ice baths, submerging patients in freezing water until they lost consciousness.

Psychiatrists previously employed ice baths, submerging patients in freezing water until they lost consciousness.

Understandably, by the start of World War II, only thirty-five psychiatrists could be counted among military ranks, but those numbers quickly rose when the psychiatric community offered its services in weeding out those they believed to be mentally unfit during the Selective Service process. Many believe psychiatrists saw the war as a means to legitimize their practice—even if it was at the expense of those defending our nation—and handsomely profiting from it.

Brigadier General William Menninger, the highest-ranking psychiatrist in the military during WWII, sought to get neuropsychiatry accepted on equal par with medicine and surgery. And it was Menninger who devised a psychiatric classification system, which scared military leaders into believing that increasing numbers of civilians were mentally unfit for military service. Even Menninger’s Commanding Officer, Colonel Sanford French, who believed psychiatry was “for the birds,” approved mental health screening, and reportedly advised Menninger that “I don’t understand what you are doing—you are changing the whole Service Command—but go ahead.”

And “change” it did. The psych screening didn’t go as predicted, as military big shots determined that the screenings had resulted in the substantial and unnecessary loss of hundreds of thousands of potential service members.

But those who made it through the psych screening were met again on the battlefield, where psychiatrists were relied upon to handle the psychological effects that training and combat situations had upon soldiers and, by the end of WWII, the number of psychiatrists in the military had risen to 1,000.

What the psychiatric community theorized from plying their trade on soldiers at the front was that the detrimental effects of “shell shock” and “combat fatigue” could be dealt with on the front lines – a mentality of dealing with issues of battle-induced stress on the front before it escalated into more debilitating symptoms and aimed at more expeditiously returning the troops to battle.

Although the results of those interventions are unclear at best, after the war, the psychiatric community transferred its new war-related psychotherapeutic treatments to the civilian population and civilian mental health intervention was born.

Psychiatrists used the war to advance their cause, testifying before Congress and sporting the authority of military uniforms to secure not only federal funds but also a new government research arm, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

In Madness and Government, by Henry Foley and Steven Sharfstein and published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA), the authors write, “testimony focused on the large number of wartime psychiatric casualties and the acute shortage of people, notably psychiatrists, trained to care for them. Much testimony was heard in praise of the new, more effective methods of care developed during the war.”

The psychiatric community’s failures, however, went unnoticed. According to Foley and Sharfstein (who at the time was on the staff of the APA), ”The extravagant claims of enthusiasts—that new treatments were highly effective, that all future potential victims of mental illness and their families would be spared the suffering, that great economies of money would soon be realized—were allowed to pass unchallenged by the professional [psychiatric] side of the professional-political leadership.”

Consequently, psychiatry became virtually the only branch of medicine to have its training subsidized by federal funds and with that came a 10-fold increase in the number of psychiatrists in the U.S. over the next forty years.

It also was with the end of the Second World War that psychiatry, with its new-found legitimacy, began to classify psychiatric conditions. Beginning in 1943 with the Surgeon General’s Medical 203 Report, the Army’s classification manual for mental health disorders, the psychiatric community had found its opening into the civilian population.

By 1952, the APA had revised Menninger’s military version of mental conditions and called it the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, known as the DSM-I, containing some 112 diagnostic categories.

Given that psychiatric diagnosing is not, nor has it ever been, based in science, the DSM-I was completely consensus-based, that is mental illnesses were added based on agreement (a vote) by fellow psychiatrists. As if consumed by some self-proclaimed supernatural clairvoyance into the inner workings of the human mind, by 1968, the APA’s psychiatrists had published a revised DSM-II listing an additional 66 new categories, bringing the total to 178.

Twelve years later, in 1980, the DSM-III boasted some 228 different diagnostic categories and by 1987, the total had risen to 259 with the publication of the DSM-III-R. By 1994 the APA was on a roll and claimed such extraordinary insight into human behavior that they expanded the diagnostic categories to 374 with the publication of the DSM-IV. Finally, by the time the DSM-IV-TR, the revised DSM-IV, had been rolled out, what originally began as a book of a mere hundred pages had grown to more than nine hundred.

For the purpose of establishing the medical integrity of the DSM (in any of its versions) the following are provided as an example of how far psychiatry has come in determining what constitutes “mental illness.”

Reading Disorder (315.00) – Reading achievement that falls substantially below expected individual chronological age. This may persist into adult life.

Mathematics Disorder (315.1) – Mathematical ability that falls substantially below expected individual chronological age. May not be apparent until the fifth grade or later.

Disorder of Written Expression (315.2) – Writing skills that fall substantially below expected individual chronological age. Little is known about its long-term prognosis.

The above “mental illnesses” along with every other mental illness listed in the DSM, were voted into existence by the APA’s psychiatrists with utter certainty (and apparent straight faces). However silly the above seem, it is the ever-expanding diagnosis of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) that Pentagon brass must familiarize itself with when considering the causes behind the epidemic of non-combat related deaths.

There is no doubt that the nation’s soldiers have been traumatically affected by their participation in America’s longest war (Iraq and Afghanistan), suffering from what many consider normal reactions to extraordinary, life-threatening situations. In fact, a recent report by the Veterans Administration reveals that 30%, or nearly 250,000 of the 834,463 Iraq and Afghanistan War veterans treated by the VA, have been diagnosed with PTSD, making it a lucrative mental illness for psychiatry.

Surprisingly, though, the psychological trauma of war does not appear to effect all soldiers, fighting in the same wars and for similar tours of duty, equally. According to a study published in the Royal Society journal by Neil Greenberg of the Academic Centre for Defence Mental Health at King’s College in London, American soldiers showed PTSD prevalence rates of in excess of 30 percent while the rates among British troops was only four percent. The study further revealed that while “researchers found increased mental health risk for American personnel sent on multiple deployments, no such connection was found in British soldiers.”

So what gives? Why are American troops returning home with a mental illness that, for the most part, seems to escape their British brothers in arms? Understanding this enormous difference in the psychological effects of war, one first has to have some history of the PTSD diagnosis.

PTSD as we know it today, was created after the Vietnam War. Originally called Post-Vietnam Syndrome, this supposed mental illness actually gained notoriety with the help of anti-war psychoanalysts unhappy with the nation’s involvement in Southeast Asia. In a 1972 New York Times article titled “Post-Vietnam Syndrome” psychiatrist and anti-war advocate, Chaim Shatan, wrote that veterans had been “deceived, used and betrayed” by the military. Shatan further expressed his opinion about the creation of this new mental illness in a memo to his colleagues, “This is an opportunity to apply our professional expertise and anti-war sentiments.”

Apparently distressed that “traumatic war neurosis” had been eliminated from the DSM-II, Shatan co-founded the Vietnam Veterans Working Group, made up of like-minded psychiatrists and succeeded in having Posttraumatic Stress Disorder included in the next edition of the DSM-III.

With each succeeding edition of the DSM, despite its controversy, the symptoms of PTSD have grown in such proportions that even many within the field have criticized the diagnosis. Herb Kutchins, Professor of Health and Human Services at California State University, Sacramento, and Stuart A. Kirk, Professor of Social Welfare, UCLA School of Public Affairs, and authors of Making Us Crazy, explained that many soldiers were not experiencing PTSD or stress, but battle fatigue—exhaustion—and that the DSM-III had gone “far beyond pathologizing the problems of war veterans,” that it “has become the label for identifying the impact of adverse events on ordinary people. This means that normal responses to catastrophic events often have been interpreted as mental disorders.”

In order to diagnose these normal responses, the psychiatric community has come up with 175 combinations of symptoms by which PTSD can be diagnosed.

But is PTSD really a mental illness in need of treatment? A brief overview of the scope of the category raises serious questions. The following are just a few of the necessary conditions needed to qualify for PTSD: experiencing traumatic events, military combat, violent personal assault (sexual assault, physical attack, robbery, mugging), kidnapping, being taken hostage, terrorist attack, torture, incarceration as a prisoner of war, natural and manmade disasters, severe automobile accidents, being diagnosed with a life-threatening illness, and repeated verbal, physical, emotional and sexual assault.

Additionally, one need not actually be the victim of the above, but also can qualify for PTSD if they are witnesses to events such as, observing serious injury or unnatural death due to violent assault, accident, war, or disaster or unexpectedly viewing a dead body or body parts. Again, the above is just an abbreviated list of conditions that may qualify as mental illness, leaving one to wonder who, whether in the military or not, wouldn’t qualify for PTSD.

Adding to the questionable, and decidedly overbroad PTSD diagnosis, the treatment associated with this “mental illness” more often than not involves the prescribing of multiple psychiatric mind-altering drugs. The very drugs that are reported to be ineffective in at least half of those diagnosed with PTSD and many now agree actually cause damage.

This kind of drugging doesn’t come cheap. The Department of Defense and Veterans Affairs reports spending nearly $2 billion since 2001 on psychiatric drugs to treat “mental illness” and PTSD, including more than $800 million on antipsychotic drugs like Risperdal and Seroquel, or “Serokill” as it is being called.

Ironically, military psychiatry’s failure to help our fighting forces provides the opportunity to demand additional research funds to “solve” the problem—much the same way as psychiatry pitched its services after WWII. Since 2006, the Army’s Medical Research and Material Command has spent nearly $300 million on 162 research programs to understand, treat and prevent PTSD. Today, however, the cause of PTSD remains elusive, as psychiatrists admit there are no known causes or cures for any mental disorder.

Despite this stunning admission, a Presidential Executive Order in August 2012 ordered the VA to hire another 1,600 mental health professionals by June of 2013. The American Psychological Association was also successful in obtaining Congressional authorization for hefty incentive bonuses for psychologists who stay on active duty, and also a recruitment incentive as high as $400,000 for an active-duty commitment of at least four years for civilian psychologists.

With the millions of dollars being spent on getting to the bottom of this “epidemic,” command may find it prudent to take a hard look at some basic facts. Suicides, and other unexplained sudden deaths, have increased for the past several years, as has the diagnosing of PTSD and the prescribing of psychiatric drugs, many of which are not approved by the FDA for treatment of PTSD and many of which cause the very symptoms the troops have sought treatment for. (See Part II – Two Soldiers Prescribed 54 Drugs: Military Mental Health “Treatment” Becomes Frankenpharmacy.)

Anyone concerned about the increasing number of deaths would be hard pressed not to notice that it actually is the diagnosing of PTSD that is at epidemic numbers. If military command continues to allow the psychiatric community to give the orders, the end result may actually be an “Army of one.”

Kelly Patricia O’Meara is an award-winning investigative reporter for the Washington Times, Insight Magazine, penning dozens of articles exposing the fraud of psychiatric diagnosis and the dangers of the psychiatric drugs—including her ground-breaking 1999 cover story, Guns & Doses, exposing the link between psychiatric drugs and acts of senseless violence. She is also the author of the highly acclaimed book, Psyched Out: How Psychiatry Sells Mental Illness and Pushes Pills that Kill. Prior to working as an investigative journalist, O’Meara spent sixteen years on Capitol Hill as a congressional staffer to four Members of Congress. She holds a B.S. in Political Science from the University of Maryland.